CDO Antonio Farias: Championing difference in service of democracy

From the time he was a young child, Antonio Farias has been acutely aware of the differences among us, as well as the many ways we navigate those differences to fulfill a common mission. Over time — during formative experiences growing up in New York City, through his time as an Army infantryman stationed in Georgia, while a student at the University of California-Berkeley and for the past 14 years as a chief diversity officer in higher education — he has observed time and again how a shared purpose can bring together people from diverse backgrounds to make extraordinary things happen.

As the University of Florida’s first chief diversity officer and senior advisor to the president, Farias holds a position on the university’s cabinet and oversees the university’s efforts to advance equity, diversity and inclusion, as well as to establish a new standard of inclusive excellence. In the announcement of his appointment, UF President Kent Fuchs lauded Farias for his track record as a diversity officer both at Wesleyan University and the U.S. Coast Guard Academy, as well as his respect at a national level.

Farias and his wife, Elizabeth García, a UF visiting professor in Latinx and feminist studies, moved to Gainesville in July, after having spent the past 14 years in snowy Connecticut. While Farias, an avid distance runner, is looking forward to no longer having to dodge snowplows on his morning runs, he is most excited about being at a university that provides a high capacity for access to higher education and great potential for truly having an impact on society.

We sat down with Farias to learn more about his background and the path that led him here, as well as his experiences since joining the university just about three months ago. Here’s what he had to say.

How did you come to be interested in diversity, equity and inclusion as a “field,” if that’s the right word? What were some of the experiences you had that led you to become interested in this kind of work?

I grew up in a very multicultural New York City environment, where on my block there were Irish Americans, Italian Americans, Puerto Ricans, African Americans, Chinese Americans, Armenians toward the end and Korean Americans. And we didn’t all get along. So I had plenty of bloody noses growing up in a very multicultural world, and for me, growing up in New York as a young boy, it was about navigating all that difference in a way that didn’t get me beat up at times.

But at the same time, we were making alliances when we all played stoop ball together, and it was about who was the best stoop ball player, not necessarily what your background was, although background always matters. So it started from the ethos of literally learning to play well together. And the only way you got to do that was to bypass all our stereotypes. Once we stopped making fun of each other or fighting with each other, we began to find some commonalities. Like we all could agree that we all hated the Red Sox. There was unity there.

What came after you finished high school?

[After working for various airlines as a jet mechanic], I joined the Army. Even though I tested off the chart in terms of aptitude, I already had a technical skill and I wanted to serve my country, so I joined the infantry. And I learned about diversity again there because I was in a foxhole in the middle of some God-forsaken jungle somewhere and the young man next to me was a Kentucky chicken farmer who had issues with who I am as a human being. And yet, we figured out how to work together because the mission was more important than our differences.

[My time in the Army] also got me out of my preconceived notions about the world. I was a city boy who was all of the sudden stationed in Fort Benning, Georgia. I had preconceived notions about what the country was and what the South was. I spent three years there, I deployed and I learned to love it. I built relationships, I learned to fish in a way I hadn’t fished before. And the Army taught me one thing I carry with me to this day: the difference you bring to a team will fall apart unless you have a common mission.

And that has informed your work to this day?

Yes, and it will be messy at times — that’s the thing. It’s not always smiles. You will get a bloody nose, whether literally or in some sort of psychological way because you are butting up against other people. And I believe in that. I believe that in order to get to that innovation, you’re going to have to create friction. And anytime you get people in the room, you’re going to have friction of some type — whether it’s geographical, whether it’s their point of view, whether it’s their racial background, whether it’s around issues of poverty or politics. So the question is how do you keep people in the room long enough for them to work out their commonalities?

You have talked about “difference in service of democracy.”

Right, that’s the “We the People” — and yes, the country was built on the backs of African slaves, and yes, women were completely excluded until 150 years later, and yes, Native Americans were decimated and their land was taken. Our historical gravesites are what we have to build on. I still believe in the bare-bones architecture of our democracy, that we can get to a more perfect union, if we face our past.

So it’s going into this democracy project with eyes wide open. How do we open up the funnel and give more people access to democracy rather than just those who have money or people who have always inherited power in this country?

So how did you end up at Berkeley?

When I left the Army, the first thing I did was drive out to California. [After a brief period in Los Angeles], I went to community college in San Diego on the GI bill and I worked at the YMCA. And I learned the University of California system is a phenomenal system in how it creates affordable access to a highly diverse population. It taught me about access, but also how opportunity can be engineered, because they had an articulation program with UC San Diego. So if you finished, you did all your requirements at the community-college level and you met the thresholds, you automatically got into the University of California, San Diego.

Because of some conversations I had with some vets from Cal-Berkeley and the encouragement of a girlfriend at the time, I thought, why not throw a Hail Mary [and apply to UC Berkeley]. And all of the sudden, I got a letter that I had been accepted. So I took the shot and went to Berkeley, and again, that was a mind-blowing experience.

You were suddenly in a very progressive environment.

I will never forget Janet Adelman’s class — Shakespeare through a feminist lens — it really rewired the way I thought about the world. Barbara Christian sparked in me a sense of duty to expand access and opportunity to those historically excluded from higher education, and she taught me how the machinery of higher education really works. Cal is also where I picked up my chops around free speech. . . . For me, free speech is a tool of the underdog. Free speech was always about those who don’t have access to power, those who don’t own the machinery, those who aren’t part of the apparatus of power, and that’s what it’s there for. So if you give up those rights, you’ve given everything up.

Do you see these kinds of conversations shifting over time?

I think there is a generational shift, and we see that in some of the surveys that have come out, where this generation thinks that issues of inclusion and diversity trump issues of free speech. That’s a marked shift from Gen X or the Boomers or the Greatest Generation. We need to pay close attention to Millennials and Gen Z instead of saying, “You’re wrong.” Free speech is not an absolute, and it has necessarily evolved and should continue to evolve to better serve our democracy.

And if it’s evolving, how do we know that we’re not the blockade to the change that needs to happen?

Right, and usually it’s us in the older generation that are the gatekeepers. If we remember our youth, it was always the older generation that was blocking the way. So, I’m open to saying I’m not seeing your point in all its complexity, your lived experience, so let’s sit down and let’s talk about this for a really long time. And that’s hard in a social media world where we talk to each other in 140 characters or we have a decontextualized “gotcha” culture where it’s like, “Oh, you said this, and therefore you must be a Nazi sympathizer. You must hate X because you said Y.” Pulled out of context, everyone is guilty of something, and that’s a challenge to finding common ground. How do you have a conversation in the public square when the public square is now social media and conversations happen asynchronously?

How much can you tell us at this point about any plans you have in your role as CDO?

The plan was not to have a master plan; that was one of things that came up when I was interviewing. I have 14 years’ experience as a CDO, but that doesn’t mean that I know UF. I am very reluctant to graft onto UF any plan that has worked elsewhere because it won’t necessarily work here. A lot of this work is around change, and that’s what we’re talking about, creating capacity for change, and change is always uncomfortable, otherwise, you’re just tweaking the status quo.

The bigger bucket is justice. How do we create a more just living-learning workspace, a more just country, a more just place where our human dignity and respect are front and center? We must treat people with the level of dignity and respect that they all deserve. Whether you’re asking for change on the street or you’re the corporate CEO, if we don’t see each others’ humanity, we’re going to always step on people and treat people with ill will.

So, I’m less concerned with what we label the change and more concerned with the mechanism of change. Most people say they want change, but they don’t want to change. They want the other person to change — ‘I want change, but I want him to change first.’ This speaks to a level of distrust that requires our attention.

Or a plan will make it change.

Right, if you just have the perfect plan, change will magically happen. But perfect diversity plans are just paper. Higher education is littered with great plans that go nowhere because the capacity and will to change isn’t really there. I can, within a week, create the perfect plan that will get us from A to Z. Will it work? No, because we haven’t developed the necessary relationships and trust built on common cause and action. So the way I know to get to change is to create relational engagement with all the stakeholders that are part of the UF system.

People have to believe that we, as a community, are capable of change and that we are capable of change because the action steps are not overwhelming. In the end, small nudges have bigger impacts than grand rhetorical flourishes.

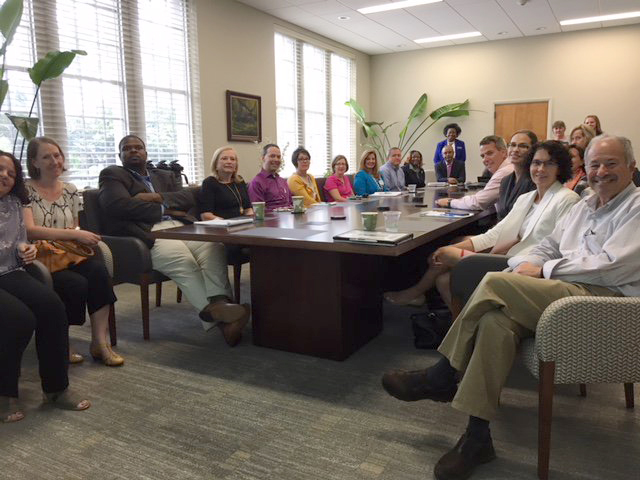

For the first 60 days, I’ve been really listening — going to various stakeholders and listening to what they have to say. Who are you? How did you get to UF? What’s really working at UF, and where do you think some of the challenges and opportunities are? Asking those core basic questions and letting people talk. And I’m taking notes, triangulating, seeing patterns emerging. And some of the patterns that are emerging are the exact patterns that I was told about when I was interviewing, which is that we are a highly decentralized organization and we need better coordination of efforts. So, that was phase one. Phase two is what I’m entering now, and it’s now bringing the diversity liaisons together and creating an enduring structure that will allow us to start shaping the climate and culture. This will be done in a transparent manner.

How do you plan to work with the diversity liaisons?

Right now, there are about 25 diversity liaisons on campus. I’ve met individually with some of them and I’m bringing all of them together. But they don’t report to me. This is all about creating a highly dynamic and horizontal network. I need to establish relationships with all the liaisons and assist them so they have the same kind of change mandate in their respective units because that’s where the network starts really getting powerful.

This is all about creating a highly communicative horizontal network. The old model was you create an org chart, there’s somebody at the top, and then you keep cascading into these bifurcating buckets, bifurcating silos. That’s just trying to replicate a centralized model that doesn’t work. It doesn’t work in this day and age, and it certainly doesn’t work at UF because we resist centralization. So, it would be foolish for me to come here with some sort of top-down approach. It won’t work. And also, I don’t want to give the impression that the CDO has the answers to everything. I can’t tell you what to do; we need to sort of figure out where we’re going together.

So, how do you work with this many people? You work with them by creating these networks that get the information flowing in and out, creating trust and then encouraging basic actions that drive intermediate goals, which get us closer to higher-level objectives. We’ll set a vision for what we mean and that vision should be audacious — it should be like we’re going to Mars. It should be something so out-of-our-reach that it may be 40 to 50 years away. Let’s face it, if we haven’t fixed the issues around justice and democracy in the past 250 years, what makes us think we can fix them in the next couple of years?

You have mentioned a sense of “belonging and presence” as being critical to our success.

Yes, and I think we can all agree on that. Now, we can start talking about how that presence and belonging shows up. How do we have crucial conversations about difference so that we actually stay at the table and I get to know your story and then I tell you my story and around this table we actually create new meaning?

If we really are a democracy, if we aspire to be a more perfect democracy, then what is our role as individual citizens to make that democracy a reality that is available to all? That’s the challenge, and UF and Florida are uniquely poised to lead.

That’s what’s exciting for me here, and I think that’s why people stay at UF. The journey is really what this is about, and you learn through the journey; diversity is not a destination. The top-five is a destination, but it’s the journey there that counts. What are we going to learn in this journey around these issues of diversity, equity and inclusion that make us Go Greater?